Works in the Collection

When Gerhard Richter fled the GDR (German Democratic Republic) and its dictated “socialist realism” in 1961, he abandoned his first painting career. He enrolled again for a second training at the art academy in Düsseldorf where he studied under Karl Otto Götz, one of the main proponents of “Informel” art, from his second semester. While Richter did not need to start from scratch in terms of technical skills, he did have to redefine himself as an artist. The situation he encountered in Düsseldorf was as follows: The prevalence of abstract art that had been the mainstay in the 1950s was waning at a progressive rate, Joseph Beuys had been appointed professor of monumental sculpture at the academy, and Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker had formed the ZERO group. As documented in Richter’s recorded notes and letters from the early 1960s (some of which are presented in detail by Armin Zweite in his publication entitled “Das Denken ist beim Malen das Malen: Gerhard Richter, Leben und Werk” (To Think in Painting is to Paint: Gerhard Richter, Life and Work), Munich 2019), these and other conflicting circumstances appeared pointless to him, interestingly boring, lacking any compelling content or tenet and therefore presented an entirely new challenge to his own mission as a painter. This was also connected to the proliferation of images in mass media, whose sheer number, sources, purpose, and function Gerhard Richter took as an opportunity to use them as source material in his experimental work. Richter himself had been very familiar with the medium of photography since his youth.

He considers photographs to be a point of reference, as they depict what the person behind the camera already selected as the defining detail of a moment, be it for magazines, daily newspapers, or private occasions. To Richter, who endeavored to reorient himself among all the artistic paths on offer, the photograph as an image depicting reality that has already been captured was extremely interesting. The worthiness of a subject to be recorded as an image has already been decided by its photographic reproduction, allowing Richter to use it as a template for further artistic processing in the medium of painting. Starting in 1962, he created his first paintings based on photographs in shades of gray, initially adding text or text fragments to some. Aside from objects (“Faltbarer Trockner” 1962; “Küchenstuhl” 1965; “Flämische Krone” 1965) and fighter jets (“XL 513” 1964; “Mustang-Staffel” 1964), they were mainly blurred depictions of people and groups of people. From 1969 onwards, his paintings on the basis of photographic templates also tied in with Richter’s decision to compile these and other photographs as well as sketches and collages into an “Atlas” by ordering and grouping the collected material and creating montages on cardboard panels in standardized sizes. As Richter continued his work on the “Atlas” over the decades, it steadily grew as a reservoir of topics and interests and ultimately manifested itself as an independent set of works whose growth has been on display at exhibitions since 1972 and which Gerhard Richter most recently compiled into a four-volume publication with around 800 panels in 2016. It becomes clear when looking at the “Atlas” that his interest in pictures extends far beyond questions of style and genre and the search for subjects. The “Atlas” rather accompanies the transition of the artistic analysis of doing justice to the medial essence of painting in the context of its creation.

The two monumental paintings that are part of the LBBW Collection, “Lilien (WVZ 516)” (260 x 200 cm) and “Claudius (WVZ 603)” (311 x 406 cm), are thus embedded into an extensive movement and development of his work that produced not only realistic paintings but also abstract canvases. The first abstract painting dates back to 1964 (CR 36-b) and the large series of gray paintings was created in the period between 1966 and 1974. In 1968, Richter painted a series of “Farbschlieren” and “Vermalungen” as well as the “Farbtafeln” starting with “Zwei Grau nebeneinander” (1966), which, in turn, represented a new way of painting. For these Richter drew upon color charts from paint manufacturers and transferred them to canvas as smoothly painted color fields in a serial grid from “Zehn Farben” (1966) to “1024 Farben” (1973). He once again used photography as a process step for creating his art in the “Ausschnitte” from 1970 and “Weiche Abstraktionen” after the mid-1970s. The “Ausschnitte” were created by taking photographs of color samples on the painter’s palette, then selecting a section of any of these photographs, transferring it to canvas on an enlarged scale, blurring and smearing it. In contrast, the “Weiche Abstraktionen” are based upon small oil paintings of which he also took photographs, selected a section, and modified it to create an abstract pictorial solution.

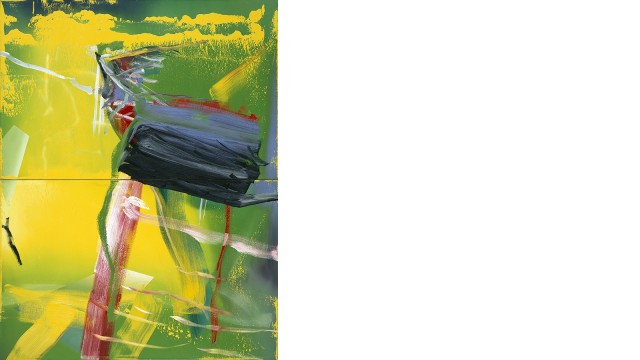

Starting at the beginning of the 1980s, Richter began to create his abstracts such as “Lilien (WVZ 516)” and “Claudius (WVZ 603)” without the photograph as an intermediate step. The large-format paintings consist of multiple layers of paint that allow the beholder to discern the tools that the artist used, such as a paintbrush, spatula, roller, and scraper. Brush strokes, scratches, and streaks resemble colored vectors that glide through a color space and intersect it against a background of monochrome surfaces. And yet the diverse overlays of the individual sections of the painting define the abstract paintings as a coherent unit. Spatial depth is also achieved through splinters of optical illusion and the contrast created by strong coloring with a yellow rain of paint splatter like in “Claudius (WVZ 603)”, but without negating the painting as a surface of artistic expression. The abstract pictures of the 1980s emerged in groups that evolved over the period of their creation and are accompanied by apparent repetitions or reflections among each other. The titles that Richter gave his paintings provide only a limited aid for understanding the paintings, as they at times point to a reality outside the painting while literally referring back to the work at other times. The paintings thereby allow the beholder to have a viewing experience without presuppositions; it is defined by interferences and depicts a reality that lies beyond conceptual determination. In his text for the catalog of the “documenta 7” exhibition, Gerhard Richter referred to his abstract paintings as “fictional models, because they make visible a reality that we can neither see nor describe, but whose existence we can postulate.”

The “Gerhard Richter Archiv” in Dresden, which was founded in 2005, includes publications, documents, unpublished writings, correspondences, and photographs, and is the central research center on the oeuvre of Gerhard Richter.

Biography

Gerhard Richter (*1932): Born in Dresden, Gerhard Richter grew up from 1935 in Reichenau and Waltersdorf in what is now the Saxon part of Upper Lusatia. While still attending school, he took evening classes in painting. After starting an apprenticeship in Zittau, he transferred to the municipal theater in Zittau in 1950 and started working as an assistant set painter. His first application to study art at the Dresden art academy was rejected. He was then hired by Dewag (Deutsche Werbe- und Anzeigengesellschaft). His second application to the academy in 1951 was accepted and Richter returned to Dresden. The curriculum included life classes, still life, figurative oil painting, art history, Russian language, politics, and economics. Lessons on art history did not extend beyond impressionism, as the GDR (German Democratic Republic) considered any subsequent art to be ‘bourgeois decadence’ (exceptions included Pablo Picasso, Renato Guttuso, and Max Beckmann). Richter joined the mural painting class and studied under Heinz Lohmar, who assisted him with obtaining permits for traveling to West Germany. He created his first large mural for the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum in 1956 as part of his thesis project (now painted over). Richter was accepted into a scheme for promising graduates run by the academy, known as the “Aspiratur”, and was commissioned to paint more murals. In 1959, he visited the “documenta 2” exhibition in Kassel. In 1961, he fled to West Berlin and applied for a second course of art studies in Düsseldorf. He enrolled in the course in 1961. Richter met Konrad Fischer (pseudonym: Konrad Lueg), Sigmar Polke, and Blinky Palermo. In 1963, he organized a one-day exhibition event entitled “Leben mit Pop – Eine Demonstration für den Kapitalistischen Realismus” at a furniture store in Düsseldorf together with Konrad Lueg. In 1964, he started working with Munich-based gallerist Heiner Friedrich and held his first solo exhibition at Alfred Schmela’s gallery in Düsseldorf; gallery exhibitions in Germany and abroad followed. In 1967, he taught as a visiting professor at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Hamburg. In 1969, he was part of a group exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. In 1971, Richter had his first retrospective solo exhibition at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen in Düsseldorf. Richter was appointed professor at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. In 1972, Richter exhibited “48 Portraits” in the German pavilion at the Venice Biennale. He was also invited to exhibit his work at “documenta 5”. In 1973, he held his first solo exhibition at Rainer Onnasch Gallery in New York. In 1977, he exhibited a retrospective at the Centre George Pompidou in Paris. In 1982, he took part in the “documenta 7” exhibition. In 1984, he took part in the exhibition entitled “Von hier aus: Zwei Monate neue deutsche Kunst in Düsseldorf” at the Messe Düsseldorf exhibition center. In 1986, he exhibited work at the “documenta 8”; he also traveled to Dresden, where his art was part of the exhibition entitled “Positionen: Malerei aus der Bundesrepublik Deutschland” at the Galerie Neue Meister, Staatliche Gemäldesammlungen Dresden. His first major retrospective in museums in Canada and the USA was held in 1988. In 1989, he taught as a visiting professor at the Städelschule art school in Frankfurt am Main. In 1994, he stepped down from his professorship at the Düsseldorf academy. The Museum of Modern Art in New York purchased the cycle “18. Oktober 1977” (1988) in 1995, after the 15 paintings had been on loan to the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt am Main for ten years. In 2002, the metropolitan chapter of Cologne Cathedral invited Richter to design a new glass window. It was completed and consecrated in 2007. The “Gerhard Richter Archiv” was established at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in 2005, and the contractual arrangement for extending the collaboration followed in 2017. Numerous major institutional solo exhibitions took place in Vienna, London, Munich, and Grenoble in 2009. He created the first “Strip” paintings in 2011. On the occasion of his 85th birthday in 2017, multiple solo exhibitions were organized around the world, including in Australia for the first time, each of which presented different aspects of his artistic work. Upon completing the three church windows for the Tholey Abbey (CR 957), Gerhard Richter officially declared the conclusion of his painter's oeuvre in 2020.